The new “Crazy Girl”: Blackpink’s Lisa performing at Crazy Horse!? — by Dr. Sidney Chan, Division of Arts and Languages

K-pop star, Lisa, a member of the internationally popular Korean girl group, Blackpink, performed at the Crazy Horse cabaret show in Paris last year. Her performance has provoked a public critical outcry on sexualisation and objectification of women. Lisa has come under great scrutiny though the comments on her decision to join Crazy Horse might be great publicity, be it negative or not, for the artist and her manager. The controversy on Lisa’s involvement in Crazy Horse cabaret performance questions her morality and her intellectuality for her career. The discussion about the Crazy Horse show reveals an interesting paradox: Does Crazy Horse empower female performers by providing a platform for them to manifest their agency when they willingly choose to be part of the show, reclaiming their bodies and subverting oppressive cultural mores surrounding female sexuality? On the other hand, is Crazy Horse inherently exploitative by reducing performers to sexual objects as its emphasis on the female body perpetuates stereotypes and reinforces the male gaze, ultimately contributing to the objectification and commodification of women?

The Controversy over the Cabaret Show

Lisa seems to remind the public that she would not allow her identity to be categorised or criticised as easily as a disempowered public figure when Crazy Horse Paris stated on its website that “a longtime fan of Crazy Horse Paris, Lisa knocked on the doors of the famous cabaret to realize her dream of joining the legendary cast of dancers.” She makes her choice to engage in the cabaret show. The Crazy Horse Cabaret Show is characterised by its sensual display of topless female bodies who perform intricate choreographed moves with elaborate costumes in a tasteful and aesthetic manner. The dancers, known as “Crazy Girls”, are presented as “proper” vessels of physical and sexual beauty, legitimately performed striptease in the theatre as the attractive and desirable.

While the narrative operates to contain female sexuality, the burlesque confronts viewers with the sight of women who are uninhibited in their sexual expression by removing clothing in a highly ritualised and styled fashion. During the show, lights are dimmed, and a sense of sanctified privacy immerses the spectators in the auditorium. The burlesque dancers on stage dismantle traditional gender roles and expectations and defies feminine passivity, virtue and domesticity by meeting the gaze of the spectators, acknowledging that gaze, and defiantly inviting them to look further. The burlesque performers appear to become symbols of women’s self-sufficiency and independence, a transgression of the boundaries of conventional image of passive female sexuality. Lisa is open to the charges of “improper” “unladylike” behaviours by posting her pictures of herself dressed in Crazy Horse costumes. The costumes feature corsets and sequins signifying blatant displays of female sexuality call into question the passive “nature” of female sexuality as it is constructed by the dominant culture. She voluntarily represents herself as a self-aware sexual being whose sexual identities can be self-constructed, self-controlled, and changing.

On the other hand, undeniably, the dancers on stage are the “objects” of gaze, of sexual desire. The question is if the attraction invokes a voyeuristic regime. In her essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Laura Mulvey discusses how female characters are represented as passive objects of male sexual desire in mainstream Hollywood films. Her theory of the male gaze suggests that the female characters on screen are displayed as physically desirable and sexually submissive, as an erotic object for both the male characters in the screen story and for the spectator within the auditorium. Therefore, some criticise the erotic, overt display of the “feminine” as an essentially sexual appeal to the audience at the Crazy Horse show is sexist objectification/fetishisation of women. The female performers’ bodily presence could be made a separate commodity that satisfies the male gaze. They pout, swing their arms and legs, bump their hips, strip off their costumes in what appears to serve no function other than to arouse and please spectators. Those dance movements become an exhibitionistic display of sexuality for erotic contemplation which fit within normative gender patterns that is based on active/male passive/female construction. The burlesque dancers are rendered powerless, objectified as a spectacle for consumption.

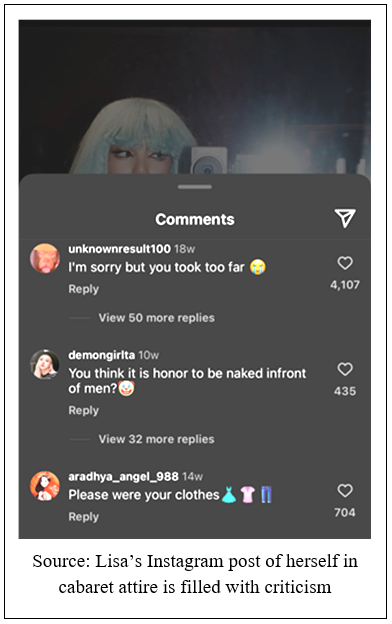

The critics view women who engage in an overt display of their bodies as inevitably and unquestionably dim-witted and improper. When they talk about stripping in a show, they immediately neglect the talents of the performers and the professional training behind the shows but always assume that the gesture of stripping in relation to a female body is already the property of patriarchy. This conception denies female performers of any active chance of articulating their own pleasures and desires, their agency of adopting the role of pure performer. Lisa is subjected to such critical derogation. Without actually watching Lisa’s performance in the Crazy Horse show, the public has already discussed how her body was paraded for male audience in an exposed and titillating manner. Her posting of her performance photos on Instagram received backlash and mockery that are revealed in some comments like, “Wow, how classy?”, “Being a stripper suits her”, “Don’t call yourself K-Pop because this is shameful”, “No matter how pretty the photos look, she is just a strip showgirl”. Lisa’s abilities as a performer are not recognised. Instead, she is located as a woman who dressed in a titillating style, suggesting an alluring provocation, would expose body parts to satiate male desires for a price. Her image is shifted from a feminine hero who used to serve as a good example to young people to a silent sexualised object, no more professionally empowered than a pretty “stripper”, the disorderly woman and her unfit conduct. Lisa is reduced to a sum of festishistic parts, scandalously scantily clad woman, rather than a metaphor of societal transgressions as an outspoken forceful woman.

The “Blackpink Lisa”. The “Crazy Horse Girl Lisa”.

What is “Lisa” indeed? Her identity is socially constructed. She becomes not only an object of desire, but she is simultaneously made a spectacle of gender identity. The costumes that Lisa wears for Blackpink or Crazy Horse are often designed to emphasise the breasts and pelvis, as signifiers of “hyper-femininity”. The visual display of Lisa the female performer—whether as a Blackpink K-pop star or a Crazy Horse burlesque dancer—is associated with the same display that calls attention to “femininity”. Such “femininity” is co-opted by capitalism and turned into a marketable commodity. Her public persona is performed, produced and exhibited that is used to sell products and services as the celebrities are “commodities, produced to be marketed in their own right or to be used to market other commodities. The celebrity’s ultimate power is to sell the commodity that is themselves” (2000, p.12). The celebrity is only an illusion and a careful marketing technique. Lisa is merely a performer for her audiences who are not interested in understanding her, but the specific version of the self, a limited version of the “Lisa” that audiences desire. Lisa is no more than a performative subject. As a celebrity, she is constantly monitored through careful observation and ultimately controlled. Lisa’s voice is not heard. Without a voice it is all the more difficult for her to reclaim her subjectivity. “Lisa”, her performative self, oscillates between the roles of being a figure of desire with trammelled sexuality and a figure of fear that is against acceptable representation of existing social norms. Lisa’s self is discursively constructed and that there is no such position of implied freedom beyond discourse.