Hong Kong’s story from the perspective of demographic history (1841-1859) — by Dr. Sammantha Ho, Division of Social Sciences

Historians have claimed that Hong Kong has a difficult story to tell because of its complicated position in colonial British history, as well as in Chinese history. Students might also find this confusing when researching different topics relating to Hong Kong.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Traditional branches of history (e.g., political history, economic history, intellectual history, etc.), not to mention the emerging paths (e.g., spatial history associated with digital humanities), add complexity to the knowledge of history. Generally speaking, history is an intellectual discipline, which examines human society and its changes over time. An intertwining relationship exists between human activities and social transformation, which mutually affects their development. Therefore, demography can serve as a mirror, reflecting the changes within a society. Combining quantitative and qualitative methods, demographic history utilizes the figures of vital statistics, population mobility, employment data, and educational statistics, which are not merely numbers but also reveal medical issues, demographic stability, economic development, and the popularization of education. This article will shed some light on the methodology of demographic history, including how to interpret demographic data and how this can help understand the history of Hong Kong in the early colonial period more effectively.

Availability of sources

The vital statistics of the early colonial period can be found in the Hong Kong Blue Book, which constitutes the financial summary and a compilation of reports relating to Hong Kong, sent back to London annually. As an important government publication, it provides all available statistics regarding public works, income and expenditure, and census returns, etc. Starting in 1844, population statistics were included in the population section of the Hong Kong Blue Book. Hard copies of the Hong Kong Blue Book are currently available in the Special Collections at the Main Library of the University of Hong Kong (HKU). The digitalized images of the Hong Kong Blue Book during the years between 1871 and 1940 have been uploaded as one of the subcategories of the Hong Kong Government Reports Online of HKU. This serves as an important and convenient online platform for studies focusing on Hong Kong, supporting researchers following the digitalization of this archival source.

Historical context

Accounting for population trends and demographic theory were concepts developed in Great Britain in the 17th century, which have since become an academic subject of practical interest to the government.1 The political meaning of demographic studies is to adjust measures, power, and the allocation of resources according to population changes. The colonial government recognized the political need for demographic statistics and promulgated the Registration and Census Ordinance in 1844. The multi-racial environment in Hong Kong necessitated the need to take effectual measures and to introduce policies charting the future direction of the colony for the sake of security and social stability. These decisions could not be made in the short term but by observing and tracking the population trend to avoid future social problems.

Although the practice of conducting population surveys had long been established in China, it was only practised for the levies of taxes and corvees. Meanwhile, the accuracy of statistics was limited to the techniques used and depended on the efficacy of governance due to the extent of the territory. For its Western counterpart, the census served different purposes since population statistics were considered “the science of the state”, necessary for accessing manpower and production capabilities nationwide and requiring scientific methods and professional technicians to ensure the accuracy of the data.2 Following the acquisition of Hong Kong Island on 26 January 1841, the colonial government conducted the first census and published the statistics in the Hong Kong Gazette on 15 May 1841. In November 1844, the first registration ordinance, the Registration and Census Ordinance, was promulgated to conduct and regularize the census process. The Census and Registration Office was established during the following year and issued the publication, “Census of Hong Kong on December 31” annually between 1844 and 1867 in the Hong Kong Gazette. However, there were missing census reports preventing a detailed interpretation of the results. In 1864, an analysis written by the Registrar General, known as the first census report of Hong Kong, was attached to the annual report, thereby establishing the practice for the following census years.

Different from the common understanding that Hong Kong had transformed into a trading port, in the first two decades of its colonial history, it was merely a British colonial outpost. The cession of Hong Kong Island and the subsequent infrastructure development gave fresh impetus to the population inflow. A large number of Chinese people came to the colony to take advantage of employment and investment opportunities. The population increased sharply from 7,450 in 1841 to 24,157 in 1845.3 However, the Chinese population mainly comprised labourers rather than merchants because the Qing government restricted the movement of the latter to Hong Kong. The affluent merchants had no desire to be ruled by a foreign power either. As regards the labouring class, the only reason for moving to the colony was employment and there was a considerable outflow of Chinese people upon completion of the infrastructure in 1848.4

The European workers desired Hong Kong’s prosperity but were disillusioned by the disturbances caused by piracy and the prevalence of diseases. In 1846, The Times reported that numerous merchants abandoned Hong Kong because of the lack of military defence facilities to ensure security.5 Hong Kong fever, a fatal disease which broke out in 1843 killed 24% and 10% of the troops and European population, respectively.6 The pandemic forced numerous European residents to depart to Macau to seek medical treatment, leading Robert Montgomery Martin, Colonial Treasurer, to lament that there were only around 60 European buildings and barely any trading firms on Hong Kong Island.7

The inflows and outflows of the population had not stabilized, hence the development of Hong Kong Island remained stagnated. Not until the outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion in Canton in 1850 and the Second Opium War (1856-1860) did the colony experience a watershed in terms of its development. Economic destruction caused by political upheavals in China brought an influx of Chinese merchants and labouring classes, especially from the neighbouring Guangdong province. The compradors who came with foreign trading firms became the elitist class in the locality. Due to the large inflow of merchants and capital, trading prospered and gradually transformed Hong Kong into an entrepôt.8 The territory of the colony was extended to the Kowloon Peninsula, which was ceded to the British as part of the colony after the Second Opium War in 1860. Wharfs and docks were expanded to Tsim Sha Tsui and Whampoa on the opposite bank of Victoria Harbour.

Classification and tabulation of figures

It is noticeable that the classification of the population was not consistent and continued to change throughout the 19th century, due to the lack of any scientific basis for classification. This problem has posed challenges not only for researchers when interpreting the demographics of this period but also for the government when attempting to understand long-term trends and changes.9 To avoid any misunderstanding, the figures should be read with caution as a result of certain inconsistencies. Between 1844 and 1867, the results of the census were shown by race, and the adult and children populations were also characterized by gender. Since numerous Chinese workers consisted of boat people, the census categorized the floating population according to the types of vessels in the various harbours. The different classifications also reflected that the colonial government was considering the practical necessity of these data. Of significance was the fact that the population was categorized by race rather than nationality until 1921, as ethnicity was used to group different individuals and thus construct socio-economic landscapes in the pre-modern society. The figures of ethnic groups were first dichotomized as “white” and “coloured”. The former represented Caucasian whilst the latter referred to the Chinese, Indian, and Malay populations. This categorization reflected that the racial composition of the Hong Kong population was less diverse, however, this was also the result of a lack of training of technicians, who were unable to standardize tabulation and project population trends.

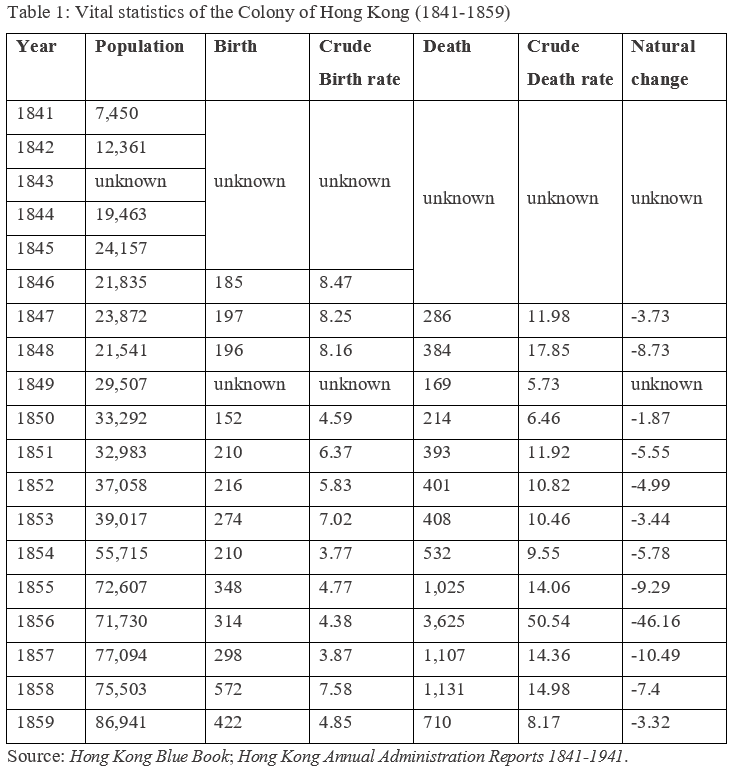

The development of population is determined by the birth rate, mortality, and mobility, which, in turn, are affected by different factors. The above elements can be calculated by natural change (the balance of known live births over known deaths) and population movement (the inflow into a territory less the outflow).10 Table 1 shows the vital statistics of the colony, including population, births, and deaths between 1841 and 1859. The crude birth rate was only around eight in the 1840s and five in the 1850s and was overwhelmed by the crude death rate. However, closer attention should be paid to the validity of the figures, even though they were published by the government. Although the Registration and Census Ordinance of 1846 ordered all Chinese residents to register information relating to births and deaths, the government recognized the difficulty of the registration of births and deaths and relied heavily on hospital records. However, on the one hand, the Chinese gave birth at home rather than in the hospitals, without reporting this to the Registry. On the other hand, there was no Chinese hospital and distrust of Western medical care prevailed. The dying, therefore, were usually found at home or i-tsz (義祠, voluntary temple) instead of at the hospitals.

Demographic setting: sojourners

The most striking characteristic of the population in the 19th century was the disproportionately high number of men in every ethnic group. From 1844 to 1859, the gender ratio (the ratio of the number of males per 1,000 females) was as high as 2,500.11 This age distribution was heavily dominated by those of working age; these young males were mainly European adventurers, soldiers, smugglers, and officials but were also made up of Chinese unskilled labour, small shopkeepers, and economic migrants.12 Since Hong Kong had been declared a free port and started establishing different infrastructures, this caused an influx of population seeking wealth, which reflected the fact that the colony was merely a temporary location for economic immigrants to make a quick profit. Workers making up this unstable population were referred to as transients or sojourners, who would neither bring their wives and settle in Hong Kong nor marry local women. Once they earned enough money or reached retirement age, they would return to their home country.

Consequently, this demographic structure resulted in a smaller number of families and, thus, a low birth rate. From 1846 to 1859, the crude birth rate was between 3.77‰ and 7.58‰,13 meaning that there were fewer than eight live births per 1,000 residents. A stable population, relying on constant age distribution, mortality, and fertility could not be constructed due to low family numbers and birth rates, as well as significant population movement.14 As a consequence of the tenuous link between the residents and Hong Kong, this had a negative impact on society in terms of the stable supply of labour. Any social or political upheaval would provoke the sudden outbound movement of the population. The outbreak of bubonic plague in 1894, for example, caused over 100,000 residents (the total population was 221,441) to leave Hong Kong.15 Since the majority were unskilled Chinese labourers and coolies working at wharves, dockyards, mines, and trading houses, the absence of this workforce could have led to immediate social and economic disorder. In the long term, the low numbers of children could not replenish the labour market as a future human resource. As a result, society plunged into a vicious cycle of relying on immigrants for the growth of the city because of the low birth rate. Following positive non-interventionism to develop trading, however, the colonial government did not seriously intend to exert territorial control over Hong Kong.16

Conclusion

When reviewing the demographic structure and social transformation of colonial Hong Kong between 1841 and 1859, it is clear that different factors intertwined to transform Hong Kong from a fishing village to a gateway connecting the West and the East. Meanwhile, the colony was also a city of sojourners in which a low birth rate and high population movement persisted throughout the 19th century. This characteristic is essential not only to understand the transformation of Hong Kong into an entrepôt but also to recognize the colonial governance over a Chinese-dominated yet multi-ethnic society. When Hong Kong was characterized as a city of sojourners, this issue raised another relevant question: when and how was the identity of the Hong Kong people constructed?

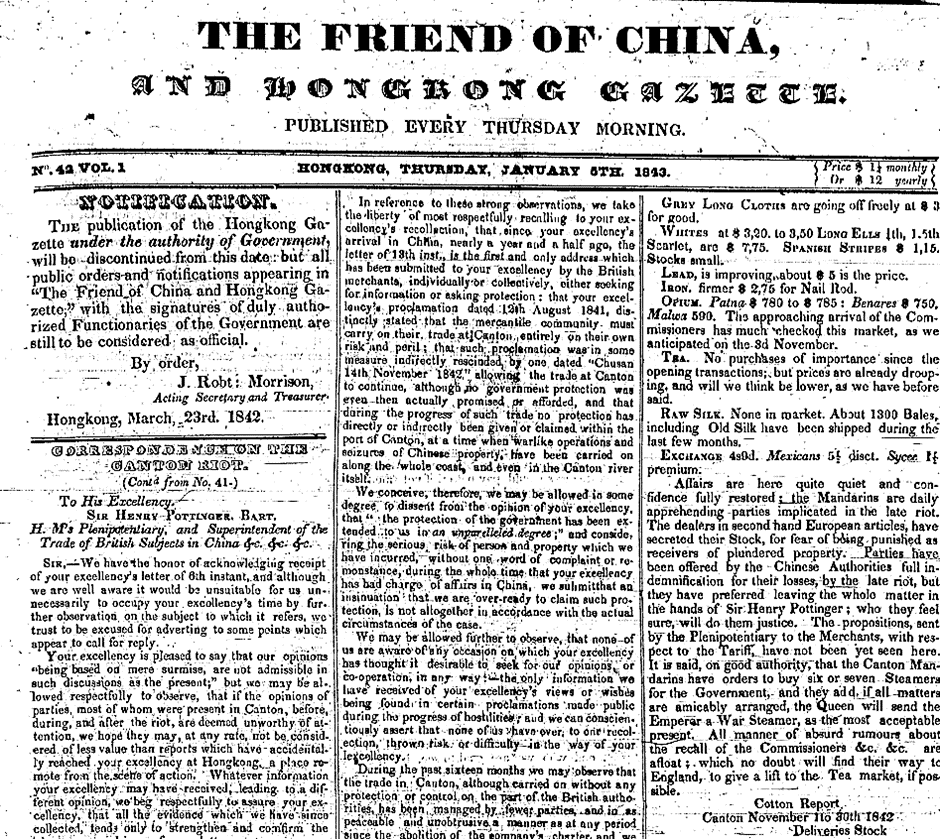

Source: https://sunzi.lib.hku.hk/hkgro/view/g1843/728506.pdf